My wife, Patty, and I were part of a recovery team sent to Thailand’s Ko Phra-Thong Island following the Great Tsunami of 26 December 2004. Both resort and village had been destroyed with great loss of life. Funerals were held on the sixth day. We departed for the island on the seventh.

Thatched homes once filled with laughter and community were now broken and silent. Entire buildings were missing, others were swallowed by sand. Personal possessions where everywhere, forgotten or useless. Of our own bungalow we found only the cement floor of the bathroom.

Patty’s and my first task was to create a basecamp in one of the few undamaged bungalows and to initiate recovery efforts. Each day we would prepare meals for a growing number of workers. Each night by candelight we would discuss our priorities for the next day, and possibilities for the coming weeks. For all of us, our real work remained unspoken: to find some measure of hope amid sadness and chaos; to honor and resurrect the dreams of our friends.

Meanwhile, our contact with the outside world was by cellphone from a beach a mile north. Each sunset we would order supplies for the next morning and hope for a possible call from family back home.

By the end of the first week we had surveyed the damages, restored electricity and brackish but running water. By the end of the second we had begun a general clean-up, securing valuable flotsam from the beach or the mangroves. It was at this time that serious exhaustion set in. Both my wife and I had begun to have nightmares, preventing any real rest from one day to the next. We were suffering from the destruction all around us, from the losses of so many we knew.

At this point, Patty returned to Canada. As for myself, I was not ready to go home, yet nor could I stay. I decided to retreat to Ko Phayam, an island further north in the Andaman Sea, one hit less hard by the tsunami. Ko Phayam has a broad and beautiful beach, Hat Yai, which faces the sunset and is cradled by cliffs overlooking coral reefs. My plan was simply to outwait the nightmares: to rest, to walk, to reconnect with the sea each day until I was healed.

It was here that I first heard tell of a sea kayaker caught in the Tsunami. It was here that I found his journal.

* * *

w.w.Lenzo spent the last fifteen years of his life exploring the shorelines of five continents by bicycle and sea kayak. All throughout he kept a journal recounting his discoveries. Coarsely bound, it was hundreds of pages long. He kept it sealed in a dry-bag beside folded nautical charts, some letters, and a copy of The Histories by Herodotus.

In the pre-dawn sleepless hours of late January, I found Lenzo’s dry-bag. It had come ashore on the new-moon tide. Imagine my surprise to find his manuscript, swollen with sand, pages wavy like the sea.

Back at my bungalow, I read with tears the fragments I could understand, the dreams I could barely decypher. The story of one man’s profound love for the sea — and the ultimate betrayal of that love, forever unwritten, perhaps unwritable.

* * *

I am told that Lenzo was spearfishing below the sea-cliffs of Ko Chang. The first wave almost drowns him with whirlpool and rip-current. Finding and recovering his kayak, he is slammed high against the rock face by the second monstrous wave. Later he is running for safety, paddling against impossible ocean currents, when the third wave, a vertical wall of water taller than his boat is long, overtakes him.

Witnesses high upon on the sea-cliffs cry out to him. One races down to the beach and into the sea, an act of love and heroism. They say that in the last moment Lenzo turned his boat, paddled straight into the onrushing stampede.

* * *

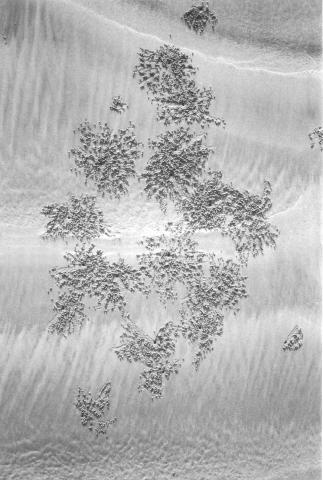

A month later, I am walking along the fine sand beach of Ao Yai, overwhelmed by the fantastic sandpaintings of the tiniest of sandcrabs. I step carefully over constellations and fortresses; move slowly so as not to disturb a butterfly or a hummingbird. A flower blooms for only an hour. A fossil, I am immobilized…

For days. For weeks. As tide after tide, twice each and every day, The Canvas is refreshed and painted anew. Slowly, I begin to understand…

Like the Sandcrabs of Ko Phayam who offer such stunning works of art to each and every tide — tiny zen masters who know of no other way to live — so too without hesitation Lenzo turned his boat, offering his life, his art to the Sea.

* * *

Lenzo’s journal is a uniquely complete work of art: in its physical form, in the way it was delivered to me, in its content, and of course in the journey reflected therein. Astonishingly, the last ten years of the journal is composed entirely of poetry. Instead of writing about the places and the people he meets, Lenzo is writing for them. Instead of letters to old friends, he is sending directly The Desert and The Sea. Indeed, Lenzo’s rare vision of seascape and solitude has become for me something of a travel-guide for both journeys: the physical and the spiritual.

All that we can know of Lenzo and his travels is in this manuscript. Foremost it is clear that Lenzo travelled alone. His is the journal of a solitary traveller passionately entwined with others. And a poetry resonant in themes of discovery and forgetfulness, of love and rebirth. His repeated use of romantic and sensual imagery transcends relationship, describes his way of “entering the world.”

Most of Lenzo’s work seems to have been composed in the moment: travel and poetry as joies de vivre. As travel is a metaphor for living, so for Lenzo poetry is a consequence of travel. His is a poetry as natural as “footprints in the sand,” unintentional yet necessary, essential.

In some way I also get the sense that Lenzo travels in order to write. If there is a searching in Lenzo’s journey, then it is in his poetry that we find tentative answers. Through writing and travel Lenzo transcends his own journey to arrive in a place of wholeness and acceptance. A homecoming he calls his forgiverance.

* * *

Upon returning to Canada, there were several practical challenges to the publication of this work. Lenzo’s handwriting was at times difficult to decypher. He moves unexpectedly through languages as diverse as Hungarian and Português, mixing voices as orthogonal as logic and love. Further, his choice of imagery is not married to his location, an infidelity flaunted by a “postmark” appended to each poem.

On a larger scale, the 15-year span of Lenzo’s journey and journal makes my role as editor and translator essentially one of biographer.

Who is Lenzo? From where has he come?

Which forces shaped his emergence as traveller and poet?

Unable to search beyond the text, I am forced to pretend an indelicate balance between what Lenzo writes of himself and what I interpret from my own vantage point. This effort to translate, interpret, add some clarity —some illusion of coherence— to Lenzo’s journey has helped me to better understand my own. Just as archeology is ultimately a kind of soul-searching, so too biography is the work of the living.

Lastly, I have received some criticism of my decision to publish Lenzo’s very private journal. However, the poetry itself, its resounding Whitmanesque declaration: “I fling my leaves!” — is response enough to my critics. Yet I invite the reader to pass judgement on this point; and if in doing so he or she shares in the mystery and inspiration which carried me home from Thailand and forward with my life, then I do believe Lenzo would be pleased. Moreover, I am convinced he would have smiled to know that his journal had been found, read aloud, repeated — if only for a short while before “the wind heals our passage over fine sand.”

Perhaps one day walking along a fine sand beach, sidestepping masterworks in bas relief, Lenzo will come upon this very edition — improved by time and passage: sand in the binding, pages wavy like the sea.

—Dr. Larry Whitlow

Saskatchewan, December 2008