It is December 2004, and southern Thailand is switching from rainy season to dry. Patricia and I ride busses south all the way from Luang Prabang, stopping for a few days each in Vientiane and Bangkok. We separate at Ranong port, from where Patricia continues by ferry to Ko Phayam, a lovely island with a perfect sunset-facing beach, and I continue by kayak, through the estuaries of the Ranong River delta and on to the rocky fortress which is Ko Chang.

Once again, I find a bungalow with wet feet and acclimatize myself to a life at sea. And below sea. Each day, I spearfish my dinner, inviting new friends to dine on curried grouper or garlic-fried coral trout, as we sit by candlelight, listening to the ocean into the night. With great pleasure, I meet again a friend from a previous trip, Max.

On the fourth day there is an unfortunate planetary concordance. The solar high-tide of winter solstice is superimposed upon the new-moon lunar high-tide. This means that the sea will be at its highest level of the year today, with correspondingly large currents and decreased visibility.

Thus, it is no surprise that while spearfishing I completely misinterpret the early signs of Tsunami.

* * *

One island further south Patricia is having lunch in Ko Phayam Village, on the protected east side of the island. Slowly, slowly the village floods to ankle depth. In a flurry, women gather up their children while troubled men work their cellphones. Leaving the confused village, Patricia heads for Chris and Chioko’s house in the island's interior. En route she meets tourists and Thais fleeing the far side of the island. She hears the word "tsunami" and starts running. But there is no way to help her husband, who spearfishes each day at exactly this time.

* * *

Because of the high tides, I’ve decided to hunt for queenfish and barracuda below the sea-cliffs on the southwestern face of Ko Chang. Arriving by kayak, I know of a sandy ledge where I can perch my boat safely above the waves. Mask and snorkel, I test myself against the currents, then swim out along the cliffs. Eyes wide, I am all peripheral vision for the flash of silver which will be a large pelagic fish, unafraid, come to check me out.

Without warning visibility goes from poor to zero. It takes a full minute to realize how vicious the currents have become — I cannot swim back to my boat! I find a cleft where I can climb above the sea. Flippers in one hand, I work my way towards the sandy ledge, which for some reason I cannot find. I am disoriented and feeling ill. I notice I have lost my harpoon. More minutes go by. Where is that ledge? The sea is unrecognizable, strange. A half-century of plastic garbage circles in whirlpools the size of parking lots. This focuses me. The sea is insanely high. The sandy ledge is underwater. My boat is gone. She's been taken out to sea.

I start searching the horizon. The sun is intense and I am feeling dizzy. When I spot my boat she is belly up, turning in the current a few hundred meters away. Mask and flippers, I arc through the whirlpool at my feet, catch my baby, roll her over, climb in. By luck is my paddle still here, tucked under a deck-line. As I return to the cliffs the sandy ledge is once again visible, just at sea level.

I hop out, empty my boat of water. Adrenaline dying, I need to rest, but I am still too nervous. I pull the boat up to a higher and larger ledge where a huge drift-tree, a meter in diameter, has come to rest. Without thinking, I moor my boat to the hardwood, drink some water, and notice that the sea has dropped precipitously. The whirlpools have disappeared. This should alarm me, but I still do not understand what is happening.

Looking up, I am hypnotized. A sinuous living thing the width of the sea, dreamlike, unthinkable. The first standing wave is here. It cannot be dangerous, I am so far above the sea. It pounds into the cliffs and climbs. Awe. It climbs. Disbelief. It climbs. Immobility.

* * *

I have heard stories that in Phuket fish were flopping about on the dry seabed moments before the standing wave arrived. Tourists ran out to play with them. Sunken treasure unveiled, I now understand the attraction of the impossible. What is shattered, what is gained.

* * *

The wave crashes over the hardwood and under. Grabs my kayak like a twig, smashes me with it against the cliff. Somehow I am still standing. The bowline has held. The hardwood log hasn’t moved, but I know that any lesser species would have given way and killed me. I am trembling.

The sea is rage incarnate. The whirlpools are biblical, unforgettable. In my boat again, I paddle through a foam of flip-flops, shampoo bottles, and fishing floats. Gradually, as my strength overcomes the currents, I feel a calmness, surely a kind of post-trauma elation, and a one-ness with my boat. I’m in no particular hurry now, playing Dorothy-in-the-Tornado as I slowly work my way back to the shallow bay I am calling home.

Fifteen minutes later, as I come around the headland, I fail to recognize that the bay is emptying of water. Rather, I am enjoying the challenge of making any headway at all. Ahead of me the beach is a mess and far too large. People are running among the trees. I am in the very center of what is left of the bay, when I hear voices calling from atop the cliffs. There is a surreal moment, when I am waving and they are calling out “wave!” Then someone changes to “BIG WAVE!” and I look over my shoulder.

* * *

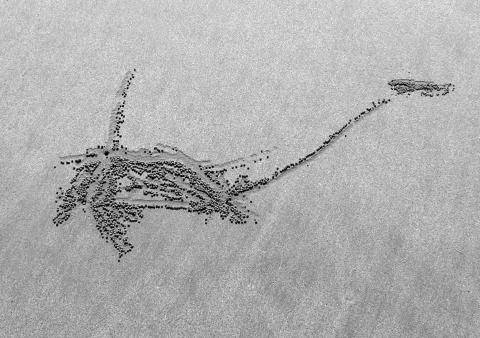

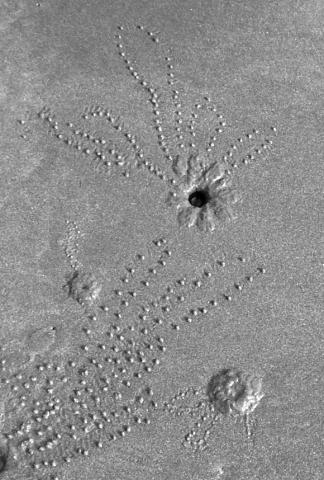

Most people think that a tsunami is a giant wave, like a surfing wave only bigger and faster. But it is not like this at all. It is better to think in terms of energy and acoustics: of sound waves bouncing and refracting. This is what my friends could see, watching from atop the island: wavefronts echoing and refracting off of islands and reefs. But unlike sound, water has both pressure and surface waves which move and echo differently. And when the source is an earthquake, there is a cacophony of wave frequencies, each travelling at slightly different speeds.

The first waves to arrive in Thailand are ultra-low frequency: oscillations of four or five meters that play out in cycles of twenty to thirty minutes. And with each surge and retreat there is an incredible current, curling around headlands, driving rips and whirlpools. Superimposed on these, and arriving later, are the large amplitude pressure waves which are hardly felt in deep water, but stand outrageously tall in the shallows. There were two of these that hit Ko Chang on that day. A smaller first one, a taller second.

And there is the shape of the wave to consider. In Hawaii, it is possible to “punch through” a giant wave and emerge from other side intact. Not only kayakers, but surfers do this constantly. The alternative is to let yourself be carried forward with the wave at high speed towards shore. Of course, this is the art of surfing, but one must punch through many waves to get far enough from shore that surfing becomes safe. Unfortunately, tsunami waves are not like this. They have no backside to emerge from. Mathematically, they are a step-function: a sideways travelling avalanche of water.

And lastly, the great majority of the casualties on this day in Thailand are not directly from drowning. Rather, as the tsunami floods the islands and mainland, people are torn from their feet and carried at high speed through buildings, trees and mangroves. The floodwater itself is only a meter and a half deep. But it is the trauma, the cuts and broken bones, that make drowning inevitable. It is not the wave, but the land, that is most dangerous.

* * *

It is incomprehensible. A sea monster. And I am so small.

But this time I don’t hesitate. I love my wife, I love this boat, and I know what I have to do. But she is so long, she doesn’t turn easily for all my strength. Backwards right, forwards left. Again. Again. Again.

I paddle hard against it, throw myself forward. Everything now is instinct and necessity. It’s impossible to stay with my boat. I let her go, and try to relax, conserve my strength, my air. I am weightless in outer space. There are a million bubbles, each pretending to know which way is up, luring me with a promise of rainbow. But I know this illusion and keep my eyes closed, one arm wrapped around my head for protection. And like a fetus, I wait.

* * *

I emerge. I am carried towards shore. I can see my boat airborne above the rocks, spinning like a pinwheel in a vertical churn of water. Each wave-trough now, my feet touch sand and I leap to the right — towards my baby. I am calling out for somebody to rescue my boat, but nobody responds. When I get into knee deep water, the Universe reverses. The steep terrain of Ko Chang is returning the water to the sea, and suddenly I am wading against the Nile. My boat comes flying past me and I catch her by her nose, planning to go with her back out to sea. But somehow my footing holds, as river upon river flows by me. A friend arrives to help and we carry my boat up the mountainside. Only now do I realize that my ankle is sprained and that somehow, through all this, my right fist has never let go my paddle.

* * *

For nine hours, Patricia has been watching satellite news with Chris and Chioko. Hour by hour the story worsens, as the magnitude of the disaster becomes known. In the tenth hour the telephone rings, her husband is alive.

* * *

Two days later, I make the crossing from Ko Chang to Ko Phayam. The outward journey carries me past the sea-cliffs where I nearly drowned. I pause to have another look at that sandy ledge, and notice that the hardwood is missing from the ledge above.

Leaving Ko Chang, I greatly regret that I did not get to see Max again. I am told that he was hurt by the second wave — that he had run down from the cliffs when he saw me in trouble. I am honored and deeply pained. I hope we will meet again one day.

Arriving in Ao Yai on Ko Phayam, Patricia is on the beach to meet me. Walks into the sea, takes my hand.